Long before modern medicine developed sophisticated anesthetics, our ancestors performed intricate surgical procedures—including trepanation, the drilling or scraping of holes into the human skull. Evidence of these operations dates back thousands of years, with skulls bearing signs of healing suggesting that many patients survived the ordeal. But how did Stone Age surgeons manage to alleviate the unbearable pain of such invasive procedures? The answer may lie in the forgotten botanical knowledge of prehistoric peoples.

A Grisly Practice with Startling Success Rates

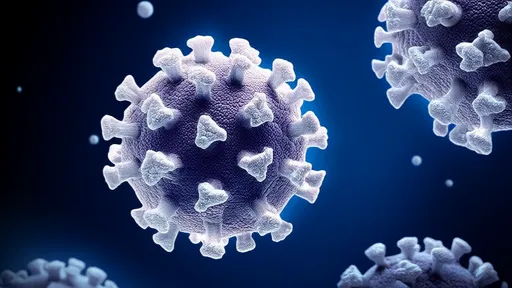

Trepanation ranks among humanity's oldest surgical practices, with archaeological finds confirming its use across continents—from Neolithic Europe to pre-Columbian Peru. What astonishes researchers isn’t just the prevalence of the procedure but its success. Examination of ancient skulls reveals that up to 80% of patients in some populations survived, based on bone regrowth around the surgical sites. This raises a compelling question: Without access to modern painkillers, how did early humans endure—and recover from—such traumatic interventions?

The absence of written records from these ancient societies means we must reconstruct their medical knowledge through indirect evidence. Ethnobotanical studies of contemporary indigenous cultures, combined with chemical analysis of residue on archaeological artifacts, suggest that early humans wielded an impressive understanding of psychoactive and analgesic plants. These natural compounds likely served as the world’s first anesthetics, dulling pain and perhaps even inducing unconsciousness during surgeries.

Nature’s Pharmacy: The Likely Candidates

Several plants stand out as prime candidates for prehistoric anesthesia. The opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), for instance, appears in the archaeological record as early as 5,700 years ago in Mediterranean regions. Its pain-relieving properties are well-documented, and residue analysis on ancient pottery suggests it was consumed as a liquid extract. In the Americas, coca leaves (source of cocaine) and tobacco—both potent pain modulators—were chewed or brewed into teas by indigenous healers.

Perhaps more intriguing are the hallucinogenic plants that may have served dual purposes. The mandrake plant, referenced in ancient texts for its sleep-inducing effects, contains scopolamine—a compound still used today in anti-nausea medications. Similarly, henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) produces hyoscyamine, which in controlled doses can induce sedation. These plants, often associated with shamanic rituals, might have been administered to patients entering a twilight state between consciousness and unconsciousness during surgeries.

The Shaman-Surgeon Connection

Modern distinctions between "doctor" and "spiritual healer" likely didn’t exist in prehistoric societies. The individuals performing trepanations probably combined practical anatomical knowledge with ritualistic practices. Ethnographic accounts of 20th-century indigenous trepanations describe ceremonies where patients consumed psychoactive brews before procedures, entering trance-like states that minimized physical discomfort. This parallels findings from Neolithic sites where hallucinogenic plant residues appear alongside surgical tools.

One theory suggests that early surgeons used plant-based concoctions not just to dull pain but to induce a form of dissociation. Plants like Syrian rue (Peganum harmala), which contains monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), could have potentiated other psychoactive substances, creating a temporary state where patients remained physically compliant yet mentally detached from the trauma of bone surgery. This would explain how patients could endure procedures that, under normal circumstances, would cause fatal shock from pain alone.

Archaeological Smoking Guns

Direct evidence linking specific plants to ancient surgeries remains elusive, but compelling clues emerge from grave goods and dental calculus analysis. In a 3,000-year-old burial site in the Balearic Islands, researchers found a skeleton with trepanation marks alongside remains of Hyoscyamus albus—a plant with strong sedative properties. Similarly, chemical analysis of hair samples from Peruvian mummies who underwent head surgeries tested positive for coca alkaloids.

Experimental archaeology has also shed light on possible techniques. Recreations using stone tools on cadaver skulls demonstrate that trepanation could take hours of continuous work. Without anesthesia, the patient’s violent movements would make precision impossible. This practical consideration strongly implies that some form of physical restraint or chemical sedation must have been employed—and plant-based solutions present the most plausible scenario.

From Ancient Remedy to Modern Mystery

Despite growing evidence, significant gaps remain in our understanding of prehistoric anesthesia. The decomposition of organic materials means we may never recover direct proof of which plants were used in specific procedures. Moreover, the synergistic effects of plant combinations—knowledge that would have been passed down orally—are lost to time. Contemporary indigenous practices offer glimpses, but centuries of cultural disruption have fragmented this ancient medical tradition.

What remains undeniable is the sophistication of early human medical practices. The successful survival rates of trepanation patients suggest that Stone Age healers possessed an empirical understanding of pain management that rivaled—and in some cases anticipated—modern medical principles. As research continues, each archaeological discovery brings us closer to reconstructing humanity’s first anesthetics, hidden in plain sight among the flora of the ancient world.

The story of Stone Age anesthesia challenges our assumptions about prehistoric peoples' technological capabilities. Far from primitive guesswork, their medicinal plant use represents one of humankind’s earliest scientific traditions—born from careful observation, experimentation, and the relentless pursuit of alleviating suffering. In an era before writing, these first surgeons left their legacy not in scrolls or tablets, but in the healed bones of their patients and the silent chemistry of plants that once bloomed at medicine’s dawn.

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025

By /Jul 28, 2025